Helping People Who lose their Homes Countries Throw Investment of projects and Their Ideas

Fundraising campaign by

sotiris Rizos

-

€0.00raised of €500,000.00 goal goal

No more donations are being accepted at this time. Please contact the campaign owner if you would like to discuss further funding opportunities

Campaign Story

Helping People Who lose their Homes Countries Throw Investment of projects and Their Ideas !

A lot of Business peoples have lost her jobs There , But They don't loose their Ideas !

Lets Take As Example Syria !

Syria’s super-rich are waiting for war to end to return and rebuild their homeland

he destruction of Syria looks as total as in any civil war of the last century: whole towns have been leveled, road and water links severed, schools and hospitals in ruins, millions of people killed or exiled and the $60bn economy left for dead.

Yet, with the conflict in its sixth year and bombs hitting government-controlled areas that previously were barely touched while airstrikes pound neighbourhoods held by rebels, the prospect of rebuilding the country isn’t daunting Syrian real estate investor Waleed Zaabi – if only a peace settlement weren’t so elusive.

“Everything is easy once you have stability,” says Mr Zaabi, 51, sipping Arabic coffee at the hotel he owns in Dubai. He describes the negotiations taking place in Geneva, in which he’s been involved, as just “a movie”.

Who will fund the dream of rebuilding Syria?

“Once you start having growth and people start to work, you’re on the right track.”

Only the most optimistic diplomats see an imminent end to the war in Syria. But when it happens, the country will need wealthy Syrian émigrésto bolster the reconstruction effort and jump-start the economy before foreign businesses consider any investment. With close to $200bn estimated to be needed to restore the economy to its prewar size, the rewards could be huge, though so could the potential losses.

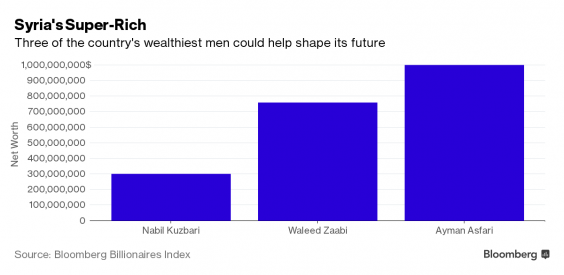

Three Names

Several names come up as possibly playing a role in shaping the country, financially and even politically.

Mr Zaabi, a member of the High Negotiations Committee meeting with the United Nations and opposed to President Bashar al-Assad, is among them.

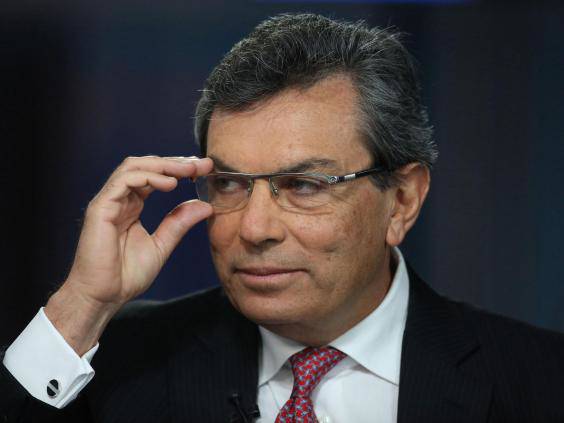

There’s also Ayman Asfari, 57, the chief executive of London-based oil services group, Petrofac, and Vienna-based, paper-manufacturing magnate Nabil Kuzbari, 79.

Mr Asfari has been an outspoken critic of President Assad, while Mr Kuzbari once had business ties to the ruling family. Mr Asfari declined requests for an interview, while Mr Kuzbari said he stands ready to invest in the “humanitarian aspect” of rebuilding Syria.

“Those investors would lend a tremendous amount of legitimacy to the reconstruction process,” says Samer Abboud, associate professor of history and political studies at Arcadia University, near Philadelphia. “There are lots of opportunities. Certainly there’s money to be made.”

Their wealth and potential influence draw comparisons to the late billionaire Prime Minister of Lebanon, Rafiq Hariri, who drove the rebuilding of Beirut and the rest of the country after its 15-year civil war ended in 1990. While Syria is complicated by the interests of Iran and Russia on the side of the Assad regime and the Saudis and US on the other, there are similarities, at least, with the task ahead for Syria.

Since protests against the regime descended into war in March 2011, at least 280,000 people have died, half the Syrian population have fled their homes and about $80bn of wealth has been erased, according to a World Bank report in April. President Assad said last week that he “will liberate every inch of Syria”.

Deadlines to reach an initial agreement this summer look less and less likely to be met and the President appears more likely to remain in power in some form. But every time there’s a hint of a possible settlement — most recently the negotiations in Geneva started with a lot of promise and a cease-fire before stalling — talk turns to the massive rebuilding effort that will be needed.

Mr Asfari said the only solution in Syria is a long transitional period, one without Mr Assad in power. In a BBC interview on 18 December, he called his country “a patient today that is bleeding and dying” and unless people see “a credible transition, then things won’t come to an end”.

He hasn’t, however, aligned himself with the fragmented opposition group. He said at a Carnegie Endowment for International Peace conference two months earlier in October that neither the “regime” nor “people in the opposition” have any political legitimacy.

Goodwill store

The son of a diplomat, Mr Asfari was raised mostly outside Syria. Educated in the US, he started working as an engineer for a contractor in Oman after graduating.

The next Omani company he worked for partnered with Petrofac in 1986 and Asfari worked his way up, amassing a personal fortune valued at $1bn in the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. Petrofac has built gas plants in Syria.

Though he doesn’t expect “paradise” after Mr Assad goes, “there is a tremendous amount of goodwill by the Syrians outside and they would want to go back and invest in their country and I’ll be the first to do that,” Mr Asfari said at the Carnegie conference.

He said there was a Syrian arrest warrant for him in 2013 over claims that he funded opponents of the Assad regime, for “supporting, you know, so-called terrorists”.

Gallery title

Mr Kuzbari, by contrast, has remained more neutral, according to Rashad al-Kattan, a political and security risk analyst and a fellow at the University of St Andrews in Scotland.

Mr Kuzbari, whose wealth stands at $300m based on the Bloomberg index, lives in Vienna and said he would reinvest in his home country.

“Syria needs trailblazing and fearless entrepreneurs who are willing to take the necessary calculated risks to rebuild the country,” Mr Kuzbari says. Return on investment “will be high, both in terms of finances as well as doing something inherently positive and constructive. I still believe that one can do good, and profit at the same time.”

Assad defect

His reception may depend on who’s in charge.

A Damascus native, he left Syria as a youth to study engineering before returning in the 1960s to take over his family’s second-generation paper business, now called Vimpex.

As recently as April 2011, he also served as chairman of Syria’s Cham Holding, a sprawling conglomerate controlled by Mr Assad’s cousin, Rami Makhlouf. It was for that association Mr Kuzbari found himself slapped with US sanctions on 18 May that year. He was removed from the list after it was deemed there was no legal merit, according to his lawyer.

For the hard-line opposition, “defecting from the regime isn’t good enough, you have to publicly state you’re against them,” said al-Kattan, whose Centre for Syrian Studies at St Andrews is partly funded by Mr Asfari’s foundation. “He hasn’t made any public statement, with or against the regime.”

Mr Zaabi, a civil engineer by training, comes from Daraa, the city where the regime’s quashing of a demonstration triggered the war. He left Syria in 1988 for a job in the United Arab Emirates that included a house, a car and 2,000 dirhams ($540) a month.

Three years later, he started his own business, building small structures with shops on the first floor and housing units on the second before growing into a company that includes real estate, contracting, hospitality, industry and education units. Mr Zaabi’s empire is now valued at more than $750m by the Bloomberg Billionaire’s Index, though he says his net worth easily exceeds $1bn.

Energy and mineral resources

Mining

Phosphates are the major minerals exploited in Syria. Production dropped sharply in the early 1990s when world demand and prices fell, but output has since increased to more than 2.4 million tons. Syria produced about 1.9% of the world's phosphate rock output and was the world's ninth ranked producer of phosphate rock in 2009.[29] Other major minerals produced in Syria include cement, gypsum, industrial sand (silica), marble, natural crude asphalt, nitrogen fertilizer, phosphate fertilizer, salt, steel, and volcanic tuff, which generally are not produced for export.[28]

Oil and natural gas

Syria is a relatively small oil producer, accounting for just 0.5 percent of the global production in 2010.[30][31] Although Syria is not a major oil exporter by Middle Eastern standards, oil is a major pillar of the economy. According to the International Monetary Fund, oil sales for 2010 were projected to generate $3.2 billion for the Syrian government and account for 25.1% of the state's revenue.[32]

Electrical generation

In 2001 Syria reportedly produced 23.3 billion kilowatt hours (kWh) of electricity and consumed 21.6 billion kWh.As of January 2002, Syria's total installed electric generating capacity was 7.6 gigawatts (GW), with fuel oil and natural gas serving as the primary energy sources and 1.5 GW generated by hydroelectric power.[28] A network totaling 45 GW linking the electric power grids of Syria, Egypt, and Jordan was completed in March 2001 Syria's electric supply capacity is an important national priority, and the government hopes to add 3,000 megawatts of power generating capacity by 2010 at a probable cost of US$2 billion, but progress has been slowed by a lack of investment capital. Power plants in Syria are undergoing intensive maintenance, and four new generating plants have been built.The power distribution network has serious problems, with transmission losses estimated as high as 25 percent of total generated capacity as a result of poor quality wires and transformer stations. A project for the expansion and upgrading of the power transmission network is scheduled for completion in 2005.

As of May 2009 it was reported that the Islamic Development Bank and the Syrian government signed an agreement stating that the bank would provide a €100 million loan for the expansion of Deir Ali power station in Syria.

Nuclear energy

Syria abandoned its plans to build a VVER-440 reactor after the Chernobyl accident.[34] The plans for a nuclear program were revived at the beginning of the 2000s when Syria negotiated with Russia to build a nuclear facility that would include a nuclear power plant and a seawater atomic desalination plant.

Industry and manufacturing

The industrial sector, which includes mining, manufacturing, construction, and petroleum, accounted for 27.3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2010 and employed about 16 percent of the labor force. The main industrial products are petroleum, textiles, food processing, beverages, tobacco, phosphate rock mining, cement, oil seeds crushing, and car assembly. Syria's manufacturing sector was largely state dominated until the 1990s, when economic reforms allowed greater local and foreign private-sector participation. Private participation remains constrained, however, by the lack of investment funds, input/output pricing limits, cumbersome customs and foreign exchange regulations, and poor marketing.[28]

Because land prices are not controlled by the state, real estate is one of the few domestic avenues for investment with realistic and safe returns. Activity in the construction sector tends to mirror changes in the economy. Investment Law No. 10 of 1991, which opened the country to foreign investment in some areas, marked the beginning of a strong revival, with growth in real terms increasing over 2001 and 2002.

Tourism

Non-Arab visitors to Syria reached 1.1 million in 2002, which includes all visitors to the country, not just tourists. The total number of Arab visitors in 2002 was 3.2 million, most from Lebanon, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq. Many Iraqi businesspeople set up ventures in Syrian ports to run import operations for Iraq, causing an increased number of Iraqis visiting Syria in 2003–4. Tourism is a potentially large foreign exchange earner and a source of economic growth. Tourism generated more than 6 percent of Syria's gross domestic product in 2000, and more reforms were discussed to increase tourism revenues. As a result of projects derived from Investment Law No. 10 of 1991, hotel bed numbers had increased 51 percent by 1999 and increased further in 2001. A plan was announced in 2002 to develop ecological tourism with visits to desert and nature preserves. Two luxury hotels opened in Damascus at the end of 2004. Since March 2011 tourism in Syria has fallen due to the ongoing civil war.

Mission and Vision

- Work to include the largest number of male and female investors and economists both inside and outside Syria to participate in supporting the revolution.

- Bring together the activities in support of the revolution.

- Carry out all activities in support of the Syrian revolution and the Syrian people while preserving the sovereignty and unity of the Syrian state, as well as the Syrian national fabric of all its components.

- Real and effective participation in the support and maintenance of the Syrian revolution in order to help it achieve its goals, and the enjoyment of their human rights of dignity and freedom.

- Cooperation and coordination with forums, associations, and institutions working in the field of economics with common visions and goals that support the Syrian revolution, or that help bring about an economic renaissance in Syria.

- Participate in the development of a vision for the Syrian economy in the next stage, and whatever is necessary in the form of studies, strategies, plans and ideas.

- Voices

Who will fund the dream of rebuilding Syria back to its former glory?

Lebanese banks are the only institutions who know how to open enough letters of credit to fund Syria’s reconstruction materials: so rebuilding Syria means big profits for them.

The rebuilding of Syria's primary cities would be a costly venture AFP

It might seem obscene, even grotesque. But the businessmen, construction giants and entrepreneurs of Lebanon are already planning the rebuilding of a physically shattered and broken nation called Syria. With at least 280,000 dead – the statistics become more wobbly the longer the civil war continues – what’s the point of talking about the nation’s restoration, you may ask? Well, who could be more expert than the men and women who have restored – not very successfully, it must be said – the glories of their own capital of Beirut after Lebanon’s 15-year civil war?

The great and the good of Lebanon’s private sector have therefore been meeting to discuss the frightening reconstruction costs of their not very lovable neighbour. The economic losses of the Syrian conflict are estimated, so far, at £185bn and, according to a Syrian consultancy, reconstruction will take between fifteen and twenty years to complete. But why wait till the end of the war? “If George Marshall could draw a plan for the reconstruction of Europe before the end of the Second World War,” Lebanon’s former economics minister says, “Lebanon must start preparing now for the reconstruction of Syria.”

Residents of Syria’s Azaz caught in the crossfire

Brave words from Nicholas Nahas, you may say, but his impatient colleagues expressed much the same optimism at a conference of businessmen in Beirut. The Lebanese are well known as the 10 per cent men of the Middle East and don’t want to be left out of the reconstruction profits once the war is over – whoever is then in charge of Syria. There are plans for a massive increase in the capacity of Beirut port and of the small harbour in the city of Tripoli and the reopening of the overgrown airport at Qlaiyat in the far north of Lebanon.

Lebanese banks – and there are seven private Lebanese banks in Syria today – are the only institutions who know how to open enough letters of credit to fund Syria’s reconstruction materials: so rebuilding Syria means big profits for them.

There’s even a steam train enthusiast in Beirut who has for more than two years been proposing a four-track electric railway from Beirut port which would speed trains through a vast tunnel in the Lebanese mountains to a marshalling yard in the Bekaa Valley – poor Baalbek, I keep thinking! – from where steel and concrete would be trucked over the anti-Lebanon range to Damascus, Homs and even Hama.

Nabil Sukkar, a development and investment analyst who was a close economic confidante of Hafez al-Assad – father of Bashar – turned up in Beirut to tell Lebanese and UN delegates that priority must be given to the reconstruction of the great Syrian motorways from Aleppo to Damascus and other cities as well as the Syrian harbours of Latakia and Tartous.

But how to blend dreams with reality? Millions of Syrians have fled the war and their children – those in Arab countries, at least – are growing up with poor or non-existent education, despite local and EU assistance. How can legions of young Syrians reconstruct their country if they cannot read or write? True, the ancient centre of Damascus has been largely spared destruction but the old city of Aleppo and its wonderful mosque – and the Ottoman heart of Homs – has been reduced to rubble.

Who will reconstruct the masterpieces of Syrian architecture?

How do we separate the truth from the lies when reporting war crimes?

Lebanese architects tried to inspire a recreated but re-imagined Beirut after their own war. They restored the French mandate streets of the 1930s but allowed the bulldozers into the Ottoman ruins. Instead of the popular soukhs that once adorned old Beirut, the new streets are packed with Parisian and Italian fashion houses whose prices only the wealthy can afford. Yet, as economist Marwan Iskandar points out, Lebanon’s expertise in schooling and hospitals on an international level should help Syria restore its education and health infrastructure.

So do the Syrians and their Lebanese assistants start with the restoration of the beauty that was destroyed – or by reconstructing the huge suburbs whose original slums housed thousands of those whose oppression and poverty inspired the 2011 revolution? There are cynics who claim, rightly, I fear, that much of the destruction has been caused to buildings, which were themselves a scandal of construction. So why not force the thousands of secret policemen to abandon their dungeons and do a proper job of rebuilding their country with their hands?

At the very least, Syria’s poor must be given homes of which they can be proud. This is an opportunity as well as a burden. But post-World War Two experience does not, despite the Marshall Plan, hold out much immediate hope. I remember the rusting, corrugated iron nissen huts that surrounded my own home town of Maidstone for years after the war, all that bankrupt Britain could afford families in the decades of austerity. Despite the reconstruction of old Warsaw, the Polish capital and the fire-bombed German city of Dresden were later packed with grey concrete slab apartment blocks which were a disgrace for generations. Syria must not suffer that fate – a recreation of the pre-civil war housing which would only reproduce the same pre-war bitterness.

READ MORE

Why the US is finally dropping its calls for Assad to go

By chance, Thomas Piketty, France’s brilliant cover-boy economist, has also just been in Beirut, explaining how the Middle East is the most economically inequitable place in the world. Only 10 per cent of its 280 million people benefit from 60 per cent of its revenues, and Isis – the enemy of the world as well as Assad – “feeds on the frustration” of this inequality. The system favoured by Saudi Arabia and Qatar, where supplicants come “to seek crumbs from the table”, does not work. Piketty favours an Arab Union based on the EU model – some hope.

But of course, the big problems remain. Who will fund the rebuilding of Syria? The Gulf States will surely refuse if Bashar remains. But Russia, China and Iran will assuredly want to put up the cash if he stays. Then it would be the Syrian émigré opposition which would be cut off from the country’s reconstruction. And the US, of course.

Or would a victorious Syrian army become the arbiter and guarantee of Syria’s economic future, whoever is the nation’s official leader? For as we all know, the world loves the military. Just look at the money we – I’m including Russia -- have poured over the years into the armies of Egypt, the Gulf, Jordan, Libya, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria and, of course, Israel. The Syrian army rebuilds the Syrian nation. A regime tautology, a cliché. But I can already imagine it on the billboards.

A lot of Business peoples have lost her jobs There , But They don't loose their Ideas !

Help Building a Crowdfunding website who users can Lend, Pledge, Equity, Donate, their projects and Ideas from all those peoples !

Organizer

- sotiris Rizos

- Munich, DE

No updates for this campaign just yet